When a .400 Batting Average Wasn’t Good Enough

Star Regulars Who Have Hit for That Fanciful Figure Over a Season’s Course and Yet Failed to Win the Batting Championship of the League

By CLIFFORD BLOODGOOD

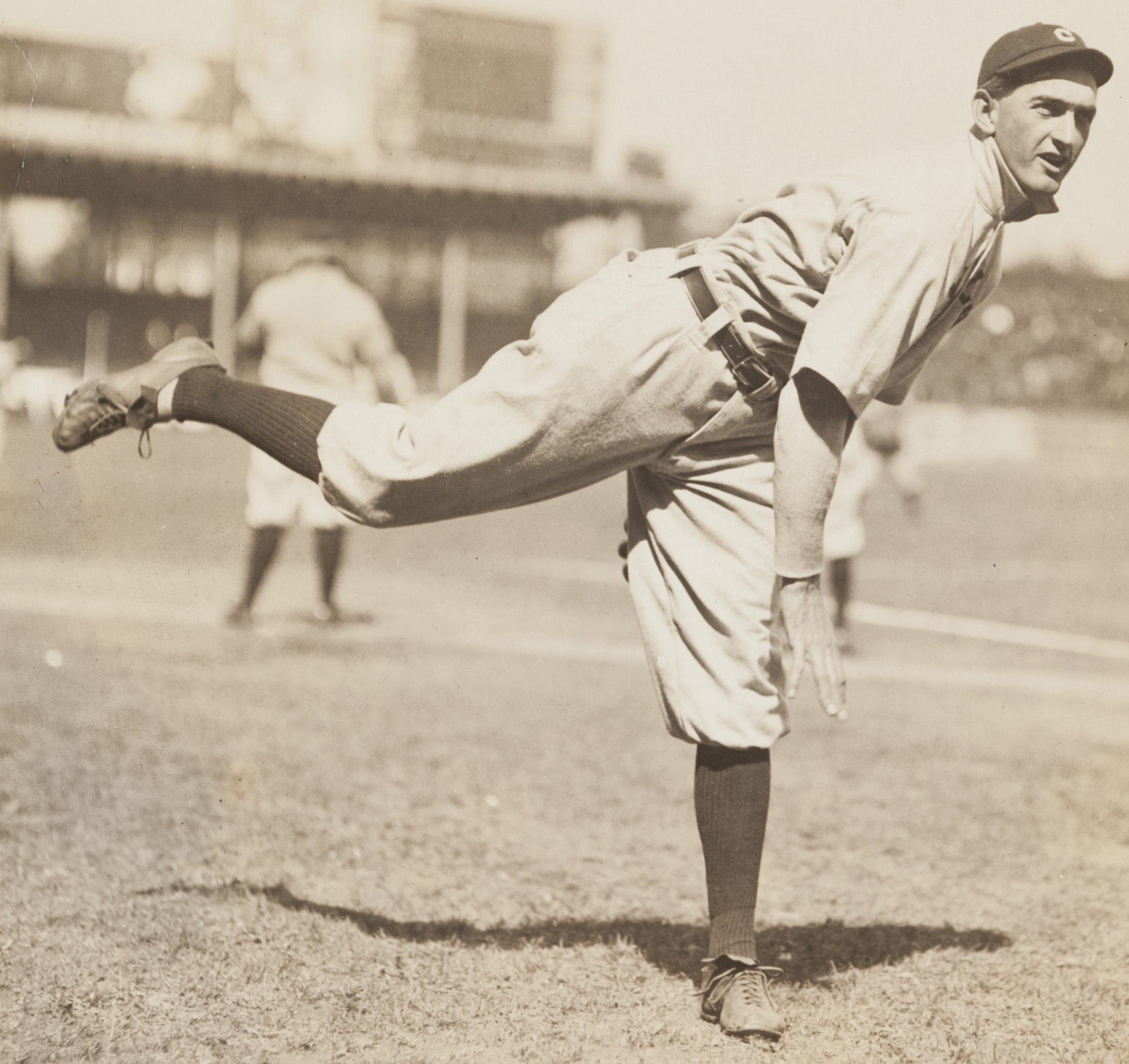

Joe Jackson, one of the greatest natural hitters ever to swing a bat, hit a lofty .408 back in 1911 but failed to win the batting championship of the American League that season

One goal that Joe DiMaggio, voted the most valuable player in the American League for 1939, had his heart set on last season was to bat .400. The season was well along and it looked as if he might make it. He was pounding the ball at a .410 clip. Then came one of those inexplicable let-downs and in a little over a week his mark had shrunk to .399. The New York sports writers made much of this drop in their daily columns which prompted one visiting player to remark with a touch of disgust in his voice, “Here’s a guy batting .399 and they say he’s in a slump. Can you beat that?”

The truth is that the great DiMaggio was in a slump and never did regain the fast stride that carried him beyond the .400 mark. He finished the season with a batting average of .381, which certainly needs no apology. It was good enough to lead the league and by a comfortable margin.

There have been players who have gone through an entire season and escaped this batting malady which sends batting averages on the skids. They have hit .400 or better and yet failed to win the hitting championship. If they don’t deserve a feature story then the automobile isn’t a common vehicle of transportation.

Joe Jackson, whom Walter Johnson said was the greatest natural hitter he had ever seen, was one of those hard luck fellows. Joe never won a major league batting championship in his life, but he was always near the top giving Ty Cobb a terrific struggle and battling Speaker. Such American League batting leaders as Buddy Myer, Lew Fonseca, Dale Alexander, Luke Appling never saw the day that they were in Jackson’s class as hitters.

He spent ten full seasons in the American League before he was ousted for the part he had allegedly played in the 1919 tussles for the championship of the baseball world. In none of those years did Jackson hit under the .300 mark and in six of them he went over the .350 figure. And, remember, in those days the pitchers used the spitter, the shine ball and other freak deliveries and balls were blackened and roughened and still kept in play.

Joe Jackson had a couple of trials with the Philadelphia Athletics and after being optioned and recalled was finally traded to the Cleveland Indians by Connie Mack. Joe’s first full season in the top bracket was 1911 when he hit a scintillating .408 but was nosed out of the batting crown by Ty Cobb, who that season hit .420, the highest average of his career.

There was nothing fluky about Jackson’s initial major league average. It was made in 147 games and he accounted for 233 hits, the highest total ever compiled by a first year man in the majors. But the speedy and inventive Cobb in 1911 cracked 248 safeties, a number he never again reached in one season.

Ty, the top Tiger, the number One man in the baseball Hall of Fame at Cooperstown, the daring dervish who established and broke record after record, who in twenty-four years of play uncorked 4,291 bingles for a life time batting average of .367, hit over .400 in three different seasons and in one of those he, too, was dished out of the batting championship.

That was in 1922 when Cobb, in 137 games, manufactured 211 hits for a percentage of .401. That year another great athlete was voted the most valuable player in the American League. George Sisler, the graceful first baseman of the St. Louis Browns. With a steady rattle of base-hits resounding from his bat he nearly made the Browns a pennant winner. Never before nor since have they been so close to the goal. George unfurled 246 bingles for a phenomenal average of .420 to lead the league.

Note the similarity of Sisler’s batting figures when he beat out Cobb and Cobb’s when he beat out Jackson. The averages are identical .420 and there are only two hits difference. Incidentally, in 1911 Cobb won the Chalmers automobile award which is comparable to the most valuable player aware copped by Sisler in ’22.

The real headache for .400 hitters, with the exception of the year when bases on balls counted as hits, was in 1894 when Hugh Duffy rang up a mark of .438 which still stands in the record books as the top achievement of all time.

Hugh was a magnificent outfielder and despite his medium build a terrific hitter who specialized in distance blows. He spent seventeen years in the big show, most of it with the Boston club, made more than 2,300 bingles for a life time average of .330. The year he took the first prize with .438 he bagged 236 hits.

Just below him in the averages was George Turner of Philadelphia, a flashy outfielder who started out to be a pitcher but thought better of it. Turner solved the National League hurling of 1894 to the tune of .423, which certainly isn’t a mark to make one hide his head in shame.

One of Turner’s teammates at the time was Ed Delehanty. Some old-timers insist that Big Ed could hit a ball as hard as Babe Ruth. There is much evidence pointing to his slugging prowess. In one game he socked four home runs and a single for a total of seventeen bases. He has the unique distinction of being the only player to lead both the American and National Leagues at bat. In 1894 Delehanty, in 114 contests, poked out 199 hits which netted him an even .400 average.

Doing even better at the plate than Delehanty in 1894 was still another Philadelphian, giving the club three .400 regulars (plus a .398 Billy Hamilton). Yet it finished the season in fourth place. Without further analysis it can be assumed that the pitching was terrible if not horrible. But we digress. The player whose average was between Turner’s and Delehanty’s was Sam Thompson.

He batted .403, a mark made on 185 safeties in 102 conflicts. There was nothing of the flash-in-the-pan about Big Sam Thompson who was the greatest home run phenom to move along the baseball trail until Babe Ruth came along. Like the Bambino he was a left-handed hitter who pulled the ball into the right field stands. Sam put in fifteen years under the big top for a grand batting percentage of .337. In ten of those seasons he bettered .300 which was a true mark of distinction in his day and in two years topped .400. He hit .406 in 1887 and didn’t win the batting championship of the league then either. That was the year when bases on balls counted as hits.

Think of it though, hitting over .400 twice and still failing to win first honors. Honus Wagner, of the bow legs and bulging shoulders, led the National League in batting percentage eight different years and never had a .400 season. If Sam Thompson ever said, “There ain’t no justice,” he could be pardoned for his views.

The name of Wagner brings to mind another Pirate favorite of the good old days. Fred Clarke, left fielder and manager of the club when it won pennants in 1901, 1902, 1903 and 1909. The hefty Kansan broke into the major leagues with a perfect day at bat, drawing four singles and a triple from the deliveries of “Cannon Ball” Gus Weyhing, one of the famous pitchers of the nineties. Right then and there some predicted a great batting career for Clarke and they weren’t wrong. Before he hung up his glove for the last time he had accumulated more than 2,700 hits. He lasted 21 years in the fastest company, eighteen as a regular.

The high mark of his brilliant career was .406 fashioned in 1897 with the Louisville club which was moved to Pittsburgh in 1900. It was the only time Fred ever hit the .400 mark over a season’s course. In 129 games he scored 122 runs, making 213 hits. But he finished second best.

The lad who beat Clarke out of the batting championship that season was “Hit ‘em where they ain’t” Willie Keeler. The Baltimore bantam launched 243 hits for a percentage of .432. This in only 128 games. Had the schedule run 154, as it does today, he might have been credited with 275 hits in one season.

A bit more detail about Keeler’s work in 1897 is not uninteresting. He hit safely in his first forty-four games of the season and was stopped on June 19th by Frank Killen, of Pittsburgh, in four attempts. On September 3rd he cracked out five singles and a triple in six times at bat. Keeler was a singles hitter mainly. In 1897 he made 199 one-baggers which is still on the books as a record. Thirty years after Keeler set the mark, Lloyd Waner, of Pittsburgh, came within one of tying it. From that alone one may readily appreciate its significance.

One of the outstanding luminaries of the baseball world in the gay nineties was Jesse Burkett, who started his career as a pitcher but turned to outfielding when he discovered the knack of pounding the ball off the outfield fences. Jesse made 2,872 major league hits. He quit playing major league ball after the 1905 season closed and until the 1922 season stood alone as the only big timer to collect three .400 batting averages.

Burkett, performing for Cleveland, led the old National League in batting in 1895 with the flowing figure of .423 and repeated the following year with a mark of .410. Then in 1899 with the St. Louis club, it was his first year with them, he pummeled the apple for a fancy .402 but had to play second fiddle to Ed Delehanty who turned in a .408. How closely that battle for supremacy was fought is found in the mute testimony of the hit column for the year. Burkett bopped 228 bingles in 138 games, Delehanty 234 in 145.

It borders on the ridiculous to hint that a .400 batter is hitting in hard luck. But here’s the evidence. Any manager in his right mind, however, would like to scare up some of those hard luck guys for his lineup.